Arthur Charles Moses, also known as “King Bobalouie,” was a formidable figure in the streets of West Compton during the early 1970s. Together with his childhood friends, Moses formed the Pirus gang, named after the street where they grew up, as a means of protection against local gangs. This band of friends started as a neighborhood watch group but would eventually evolve into one of the first known Bloods gangs, known for their violent reputation.

In a 2017 interview with YouTube gang historian Kevin “Kev Mac” McIntosh, Moses recounted a harrowing tale of seeking revenge after his cousin was assaulted. Determined to even the score, Moses confronted his cousin’s attacker at Centennial High School, only to be ambushed by a group of Compton Crips. Undeterred, Moses regrouped with his friends and retaliated, showcasing his fearless nature and unwavering loyalty to his crew.

Over time, the Pirus’ activities escalated from street fights to more serious crimes like murder, robbery, and drug dealing. Despite his involvement in gang life, Moses also pursued his passion for music, landing a gig as a backup singer for the Delfonics. His dual identity as both a hardened gang member and a soulful crooner highlighted the complexity of his character.

Moses’ legacy extends beyond his gang affiliation, leaving behind eight children and 10 grandchildren upon his death at the age of 68. His lifelong friend, Skipp Townsend, reminisced about their time together in a high-security jail module designated for young Black men labeled as Bloods. Despite the harsh conditions, Moses found solace in his singing talent, often entertaining his fellow inmates with impromptu performances.

Sandra, Moses’ sister, shared intimate memories of her brother, revealing a multifaceted individual who was both a troublemaker and a compassionate soul. Despite his involvement in criminal activities, Moses had a softer side, bonding with his sister over music and cooking. Sandra vividly recalled a moment when she refused to bail him out of a fight, teaching him a valuable lesson about facing his challenges head-on.

As an expert explains, the origins of Black gangs in the 1950s and ’60s were rooted in community defense against systemic oppression. These early groups, while engaged in criminal behavior, primarily focused on protecting their neighborhoods from external threats. However, the influx of crack cocaine in the 1980s drastically changed the landscape of gang activity, leading to a surge in violence and criminal enterprises.

Moses’ journey from Houston to Los Angeles mirrored the experiences of many African Americans seeking a better life in the face of racial discrimination. His involvement with the Avenues gang and subsequent transition to the Pirus underscored the allure of gang life for disenfranchised youth seeking power and respect. Despite the challenges he faced, Moses played a pivotal role in the formation of the Bloods, bridging the gap between rival factions and asserting his independence.

Today, Moses’ contributions to gang culture remain a subject of debate among historians and community members. While some may view him solely through the lens of his criminal activities, others recognize his role in unifying disparate groups under the Bloods banner. Townsend emphasizes Moses’ ability to bring people together, transcending gang affiliations and fostering a sense of solidarity among his peers.

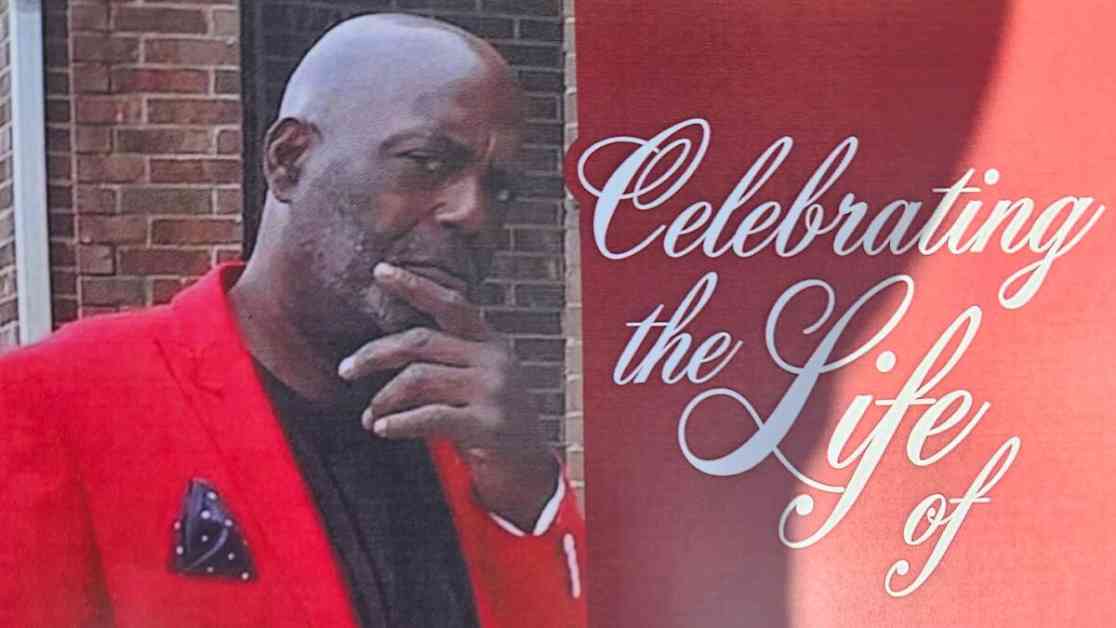

In conclusion, Arthur Charles Moses, aka “King Bobalouie,” leaves behind a complex legacy that defies easy categorization. His story serves as a reminder of the human complexity that exists within even the most notorious figures, showcasing both the darkness and light that reside in all of us. As we reflect on his life, we are reminded of the enduring impact one individual can have, for better or for worse, on the communities they inhabit.