The victory point for the location goes to the Conservatives. The party presented its election manifesto for the upcoming vote on parliament and government in Great Britain on Tuesday at the Formula 1 race track in Silverstone. The opposition Labour Party chose a much less glamorous stage on Thursday, with the headquarters of the cooperative retail chain Co-operative Group in Manchester.

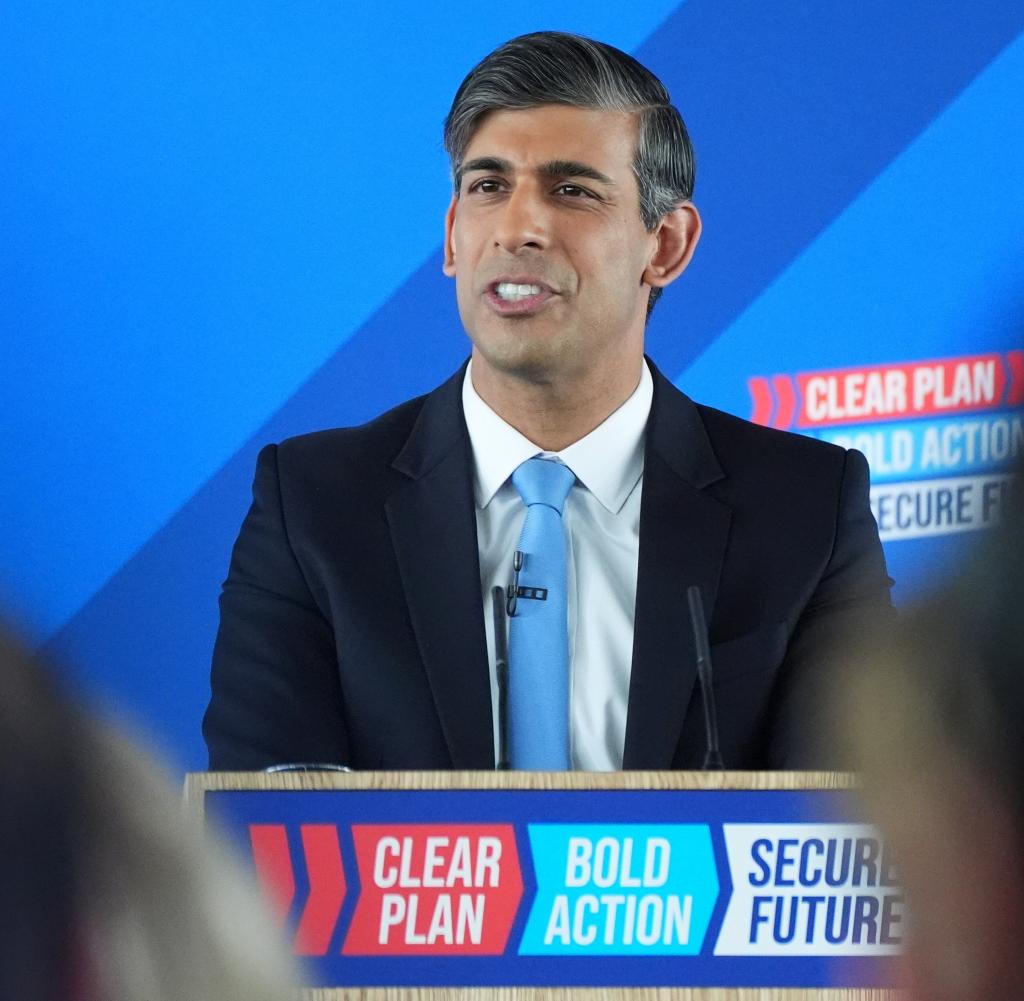

Economic growth is a key focus of the two major British parties ahead of the July 4 election. Prime Minister Rishi Sunak’s Conservative Party, which has governed the country for 14 years, is promising a “clear plan, bold action, secure future”. The party is focusing on tax cuts worth £17 billion (€20.2 billion), which are intended to benefit small business owners, pensioners and those buying their first home.

The Labour Party has proposed “change” as the heading of its programme and has announced that it will improve the economic situation of the population. “Creating wealth is our top priority. (…) We are pro-business and for the working population. A plan to create growth,” said party leader Keir Starmer. Taxes also play an important role for Labour. The party promises that the tax burden on employees will not change.

The British economy has been struggling with weak growth rates for years, exacerbated by extremely meager progress in productivity. Politicians regularly warn that the Polish economy could soon be larger than that of the UK if the growth trends of recent years in both countries continue.

Growth is crucial to boost the stagnating, and in some cases declining, standard of living. But it is also crucial to implement planned tax and spending plans. According to the opinion polls, the planned Labour reforms will most likely come into effect from next month. The party has been in the lead in voters’ favor for a year and a half, by more than 20 percentage points.

It is not surprising that Labour’s programme does not contain any major surprises. “For Labour, it seems that less is more: if you carry a Ming vase across a polished floor, you would not want to be juggling anything else,” said Sarah Coles, analyst at Hargreaves Lansdown.

Starmer and his shadow cabinet have repeatedly stressed that they will not raise income taxes, social security contributions or VAT. However, other areas will have to prepare for higher taxes and levies. An additional £8.6 billion per year is to flow into the coffers to initiate a decade of “national renewal”.

The special tax treatment of so-called non-domiciled people, people who live in the UK but do not consider the country their home, is to be abolished completely, as is the VAT exemption for private school fees. The taxes that directors of private equity firms pay on profits from successful deals will be increased, as will the special taxes on the profits of oil and gas companies.

The party had already announced most of the measures outlined in the 134 pages of its election manifesto: These included additional spending of almost ten billion pounds a year, including for the recruitment of thousands of teachers and significantly more appointments in the state health system to reduce the backlog of medical care that has built up over the years.

Starmer himself admitted that he had not delivered any surprises with the Labour election manifesto and had not pulled a rabbit out of the hat. “I am running as a candidate for the post of Prime Minister, not as a ringmaster.”

If he wins the election, Sunak has promised a further reduction in social security contributions, financed in part by a significant cut in welfare payments of 12 billion pounds. He also promised to increase defence spending to 2.5 per cent of gross domestic product and to impose an annual cap on immigration.

But economists are convinced that neither programme will solve the major problems facing the British economy. “Both parties are only tinkering around at the edges,” said Stephen Millard, deputy director of the National Institute of Economic and Social Research (NIESR). The weak economic performance of recent years has led to a significant backlog of reforms.

Investments in public infrastructure, the health system and education have long been neglected. The current fiscal limits, which both parties want to adhere to, will not solve the problems. “We will need additional spending, and that means either higher taxes or higher debt or both.”

In order for Labour to deliver the promised change, “capital has to be on the table,” said Paul Johnson, head of the think tank Institute for Fiscal Studies. He praised the focus on growth, but said it would take time for this to take hold. The election manifesto does promise a variety of strategies to tackle the country’s problems. But “the election manifesto gives no indication that there is a plan as to where the money will come from to finance this.”

Johnson’s assessment of the Conservatives’ programme was no better. The party promised lower taxes and higher spending. “These are clear promises, financed by uncertain, unspecific savings. Forgive my scepticism.”

At least Labour has managed to convince numerous business representatives of its programme. In the City, the designated finance minister Rachel Reeves is seen as a reliable economist who is committed to a solid budget.

“Only Labour is capable of improving the dire situation that the country’s economic development has taken,” said Richard Walker, CEO of the supermarket chain Iceland, as one of the speakers at the presentation of Labour’s election manifesto. Until last year, Walker was a member of the Conservatives and a regular donor. But no new ideas can be expected from the party.