Since joining Thyssenkrupp, Daniel Křetínský has been a much-discussed investor in Germany. The Czech billionaire has a 20 percent stake in the group’s steel division. The list of his companies is long. Deals with brown coal, gas, renewable energy and nuclear power plants in the Czech Republic, Great Britain, Italy and Slovakia were the beginning.

In Germany, he owns shares in the food wholesaler Metro, in the USA in the sporting goods group Foot Locker and in Great Britain in the supermarket chain Sainsbury’s. In addition to football clubs such as Sparta Prague and West Ham United from the British Premier League, the 48-year-old Křetínský also owns media companies in the Czech Republic and France. According to Forbes magazine, his fortune is around ten billion dollars.

Now another majority takeover could be on the way, and there is no precedent for this, at least in Europe: billionaire Křetínský wants to buy the British Royal Mail, including the associated parcel service GLS. He currently owns 28 percent of the shares, and the rest of the former state postal service, which is listed on the London Stock Exchange, is widely diversified.

A takeover offer for these shares has been made, and Křetínský wants to pay the shareholders the equivalent of around 4.3 billion euros. Royal Mail’s parent company has approved the offer. If the plan is successful, Křetínský will control the 508-year-old Royal Mail, including its 110,000 postmen and the supply of letters and parcels to the United Kingdom.

Takeovers by private investors have already occurred in the state-owned energy or water supply sector. But not in a national postal company: As in France, Italy or Spain, the postal service is either still state-owned. Or, as in Germany, it has been privatized on the stock exchange, but the state has retained its position as a major shareholder.

However, this case, where a single person could acquire a large postal company with his investment company and thereby gain significant influence over its infrastructure tasks for a country, is uncharted territory. The management of Deutsche Post will certainly be following developments closely, as a parallel to local postal services in the coming years cannot be ruled out.

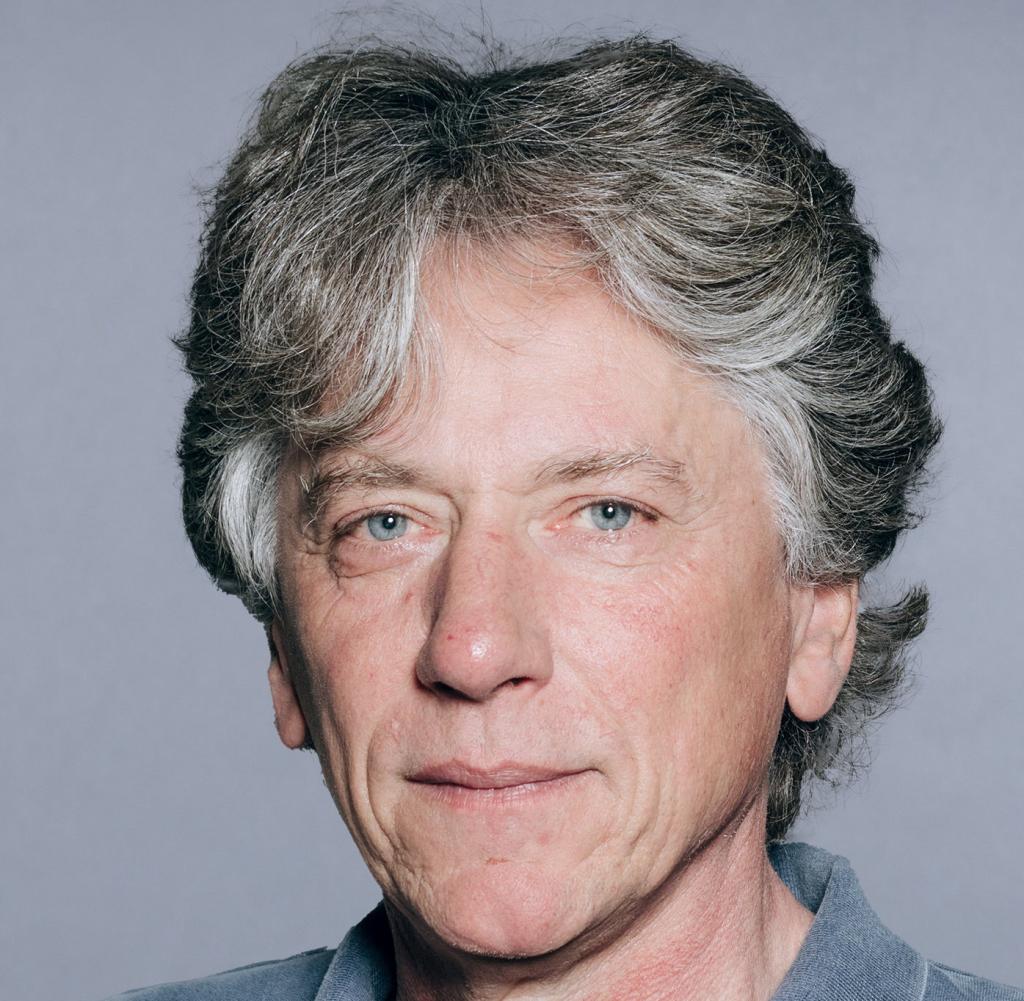

An expert who knows the subject better than almost anyone else puts the plans into context. “This takeover would have an impact on other European countries. It would send a signal that a national postal company is no longer an untouchable element of a state infrastructure,” says Rico Back, who was CEO of Royal Mail until 2020 and before that was the long-time head of the European parcel service GLS. The states still retain their influence on postal services. “A national postal service has never become the property of a single company,” says 69-year-old Back.

The British government can still reject the takeover of Royal Mail by Křetínský’s investment company EP Global Commerce, even if the postal company no longer belongs to the state. “Then the only question is who wants to invest in Royal Mail at all,” says Back. According to his analysis, the loss-making Royal Mail would have to halve the costs of parcel delivery and limit letter delivery to fewer working days in order to be able to make a profit again. Instead of six days a week as is the case today, there is discussion in Great Britain about delivering letters and parcels on three days.

So far, the government in London has not raised any objections or even stopped the process of taking over Royal Mail by Křetínský. The investor has made commitments to maintain the unity of Royal Mail and to preserve jobs. In addition, there is widespread recognition in Great Britain that a lot of things need to change in the state of the national postal service. The company is not only doing badly financially. The British are particularly annoyed by the unreliability of postal delivery.

“I think it is more likely that the investor Křetínský will succeed in the takeover than that it will not happen,” says former Royal Mail boss Back. After all, the offered purchase price per share is significantly higher than the average share price of the past few months and is “acceptable”.

The discussion also concerns what tasks a state must retain. “Should it subsidise national letter delivery or would it be better to sell it to a financially strong investor and use the money to strengthen its health system or its army?” Back asks the rhetorical question.

This question also arises in other countries. Deutsche Post, which is known on the stock exchange as DHL, achieves significantly lower profits in national letter and parcel delivery than in the international divisions DHL Express or DHL Global Forwarding. For years there has been discussion about whether the letter business, which has little future potential, should be separated from the rest of the group. Most recently, Cornelia Zimmermann of Deka Investment raised the question at the annual general meeting in Bonn.

This also needs to be put into context. “In the future, a postal company that has undervalued parts of the group will probably come under even greater pressure,” says postal expert Back. This would attract investors to take over and optimize such a company. “In the end, we would be left with a distressed mail service for which investment funds can only be obtained after regulatory changes,” says Back.

The investor Křetínský’s interest in the deal may have this background. With his current offer, the Czech entrepreneur would ultimately get the Europe-wide parcel service GLS and the letter delivery service Royal Mail for free. The purchase price offered corresponds to the current market value of GLS. “If Křetínský then succeeds in turning Royal Mail into a profitable postal company, this increase in value would be his personal gain from the takeover,” says Back.